AI. It’s totally the buzzword right now, and not in a “Hal, open the pod bay doors” sort of way. If you’re a C-level executive, you’ve probably been exposed to lots of vendors over the years who’ve talked about AI, and it might be easy to dismiss this current wave as yet another fad that’ll fade away in the near future, only to be replaced by another fad in a few years.

Not so. The current wave of AI products has a lot of value for your business, but can also bring a lot of risk to you. To help you understand the value and the risk, we’ve put together this quick primer on all things AI. Part I isn’t about AI at all – it’s entirely about human intelligence, to give you a working model to think about how you think. It’s not meant to be perfectly accurate – there’s a lot of details of cognition that we’re going to elide over – but rather, a model for understanding how humans think. Part II will apply that human intelligence model onto organizations, possibly straining it a bit, so we can understand how to decompose human decision-making into multi-person decision-making. Part III takes that model of human and organizational intelligence and maps it over to the various categories of AI. Hopefully, you understand how to leverage human intelligence in your enterprise, and you can think of using AI to augment humans in various workflows. Part IV will look at some of the hot AI products on the market, and how they leverage different categories of AI, and also considers some of the risks associated with your use of those technologies. And finally, Part V explores how we at Orca are using AI within our own products to better augment your security team.

Part I: Humans

Do humans think? Not most of the time.

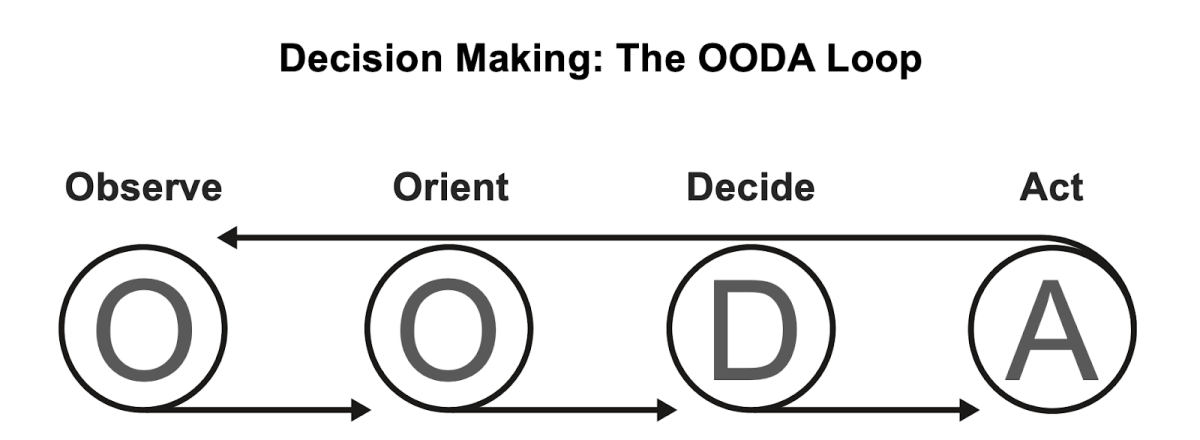

Colonel John Boyd conceived a model for human decision making called the OODA Loop. Humans observe a change in the environment. They orient themselves, assessing that change with their model of the world. They decide how to respond. And finally, they act. And, since it’s a loop, they return to observing the world, waiting for a change.

Graphic of the OODA Loop of Decision Making

Now, that probably sounds really slow. If humans actually thought about most of their decisions, we’d be wasting a lot of energy, so we’ve evolved subsystems that let us operate our decision making process without consciously thinking about it. Every day, we make thousands of decisions – from tying our shoes to eating food to driving to greeting other people – without consciously thinking about our choices. Daniel Kahneman, in Thinking, Fast and Slow refers to this as “System 1”, when we can engage in activities without wasting higher thought processes (System 2 is when we do have to engage in higher brain function, and increased calorie consumption). We’ll come back to Kahneman’s systems in a little bit; first, let’s explore the OODA Loop.

Observe

The set of human intelligence subsystems involved early in the OODA loop are selective signal enhancement – our information capture, processing, and recognition systems. We are bombarded with eleven millions of bits of information every second, but can only process… sixteen (The User Illusion, Tor Nørretranders). We can look at our evolution cousins to see the evolution of our information processing systems.

The jellyfish hydra (evolutionary split: 700 million years ago) doesn’t do signal selection at all. If you poke it anywhere, it elicits the same response. Since it can either flex or remain still, this makes sense for the hydra: it goes straight from observing (“I’ve been contacted”) through orientation (“something might be about to eat me”) to deciding (“If I don’t move, I’ll certainly die”) to action (“flex and hope I move away from the threat”).

Arthropods (evolutionary split: 600 million years ago) highlight the development of hardware signal splitting: multi-faceted eyes to enable it to only focus on one thing at a time, without needing to spend valuable and scarce cognitive resources on paying attention to all of the complexities of the world; instead, once a task is selected, the spotlight of attention becomes fixed.

Orient

But we’re processing millions of bits of information about the world every second. While some of those bits collect together into something interesting – a child running into the street requires decision and action – most of those bits are entirely uninteresting.

Vertebrates (evolving 520 million years ago) possess the tectum, which enables centralized control of attention: the ability to focus all of our senses onto the same object. What makes this processing efficient is the tectum’s ability to model the world, how we perceive it, and how our actions will affect our perception. When you reach for an object, your attention isn’t drawn to your hand moving, because your brain has already predicted the motion, and filtered it out from its inputs of “interesting things that are happening.”

Theory of Mind starts to become another model for higher life forms – birds, predators, and especially humans – the ability to understand that other actors exist in the world, and place the information we’re observing into the context of what we expect them to do. At a simple level, we often assume that others act exactly as we think we would, but as we understand the world more, we can do better at modeling people as individuals distinct from just poor clones of ourselves.

When we see behaviors that match our models, we quickly discard them from consideration. While driving, cars that stay in their lane, pedestrians walking on the sidewalk, and even birds flying by are quickly ignored, but that aforementioned child running after a ball in the street becomes something that we need to decide what to do about.

Decide (and Act)

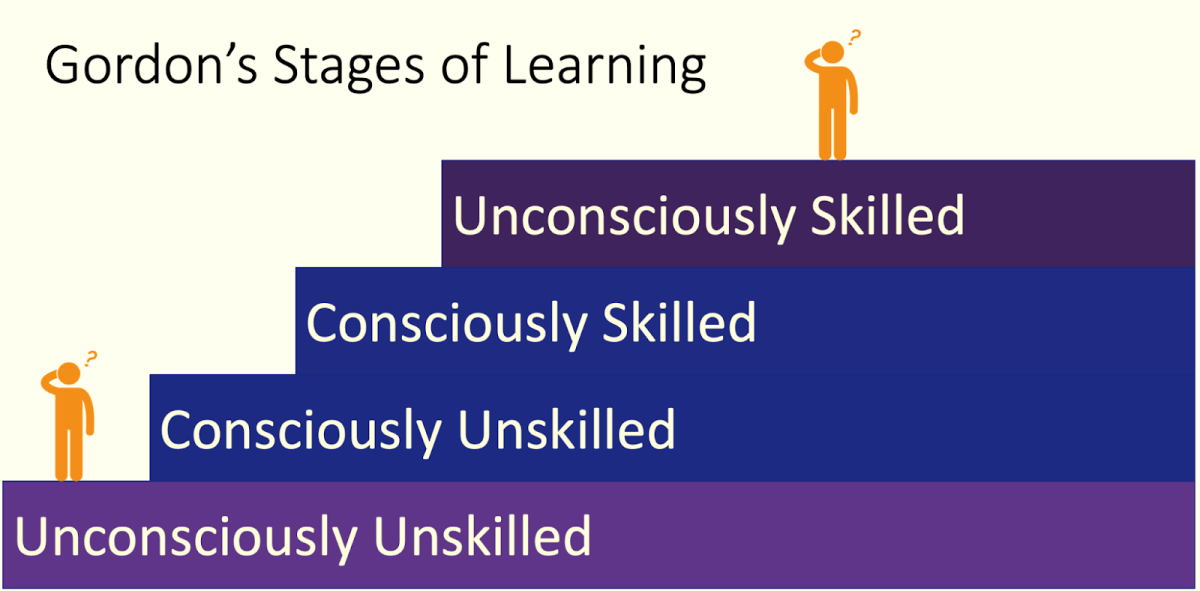

Once you’ve oriented yourself to a situation, you’re faced with a set of choices: what should you do about it? Some sets of possibilities are completely inconceivable to you: you’ve never practiced or even thought about practicing them, and so your decision set is constrained away from those options. Generally, most people are deciding from a limited playbook. We can look at most of our choices as clustered within Gordon’s skill development ladder.

Graphic of Gordon’s Skill Development Ladder

Gordon’s is more relevant for the act stage of the OODA Loop, but we’re going to explore it within the decide stage because it first captures our choice set.

When we are unconsciously skilled, there are routine choices that we’ve made in advance, and practiced, and so we spend almost no time on the decision. We rarely decide how to tie our shoes. Since we know how to take an action, we can just take it. We swerve when a child runs into the street near us, and brake if they’re farther away. We don’t think about which of those two choices to take at this level.

When we are consciously skilled, we know how to take an action, and we’ve practiced it, but it requires us to consciously engage in the task. Parallel parking comes to mind; but any task that you have to stop and think about how to do it will fit here. We might not always have a perfect match between a situation and our skills, so we might need to choose between them. If you’re not a trained first responder, coming up on a rural accident scene might trigger the need to choose between avoiding it, directly assisting, or helping with an ancillary task (like directing traffic). Each of those options is something that we can muddle our way through, but requires us to consciously decide to do them.

When we are consciously unskilled, we know that an action is a reasonable response to the situation, and we know that we don’t know how to do it … yet. These are actions that we generally won’t choose to take, but we might choose to find someone else to help or take the action for us.

And finally, sometimes we are unconsciously unskilled. There are a set of actions that we don’t even know are possible, so we don’t consider them. Sometimes we think we have a relevant skill, but we’re wrong in a dangerous way, so an action will (justifiably) appear reckless to an informed observer.

So how do we decide between this giant slate of possible actions? Sometimes, Kahneman’s System 1 comes into play: we observe something, our brain quickly orients without conscious cognition to the action that we’ve trained ourselves to do, and we “decide” to take that action. We save a lot of time and calories this way, so it should be no surprise that not only do most of our decisions get made like this, but our brain is actively seeking ways to make more decisions this way!

[Aside: Have you ever been in a seminar where the speaker “tricked” the audience into saying something predictable, but wrong? Maybe you were asked a math question specifically worded to elicit a wrong answer, or asked a series of questions to “prime” you, and then asked a trick question. What underlies most of these cognitive party tricks in the brain’s ability to rapidly engage System 1, quickly training it to make decisions and take actions without thought.]

There are two basic schools of thought on how humans actually make decisions. The rationalist school says that humans can actually examine and make rational decisions, and usually do, consciously weighing their choices. The naturalist school, on the other hand, suggests that most of the time, humans very quickly jump to a choice without conscious thought, and the conscious thought afterwards is more of a self-justification of our gut decision. Whether the rationalists or the naturalists are more wrong isn’t really relevant for us yet.

Part II

Now that we’ve explored a bit about how humans make decisions, in our next blog post, we look a bit deeper into the mysteries of organizations before wrapping this up with a look into AI.