At RSAC 2023, Oren Sade and I will be presenting a delightful talk about how to take a technical analysis – in this case, attack graphs – and convert the stories they tell into narratives that can drive strategic initiatives. If you’d like a preview of the slides, here they are. In addition to our talk, you can also get more information about what Orca is doing at RSAC.

One of the biggest communication gaps I see in the security industry exists between technical security staff and business executives. In theory (and hopefully, in practice), one of the jobs of security executives is to bridge that gap and provide a translation service between all of the stakeholders. Sometimes, translations leak, and since they’re all in English (or whatever your corporate language is), a technical stakeholder gets confused about how a very clear description of an attack path gets glossed over and turned into a vague initiative.

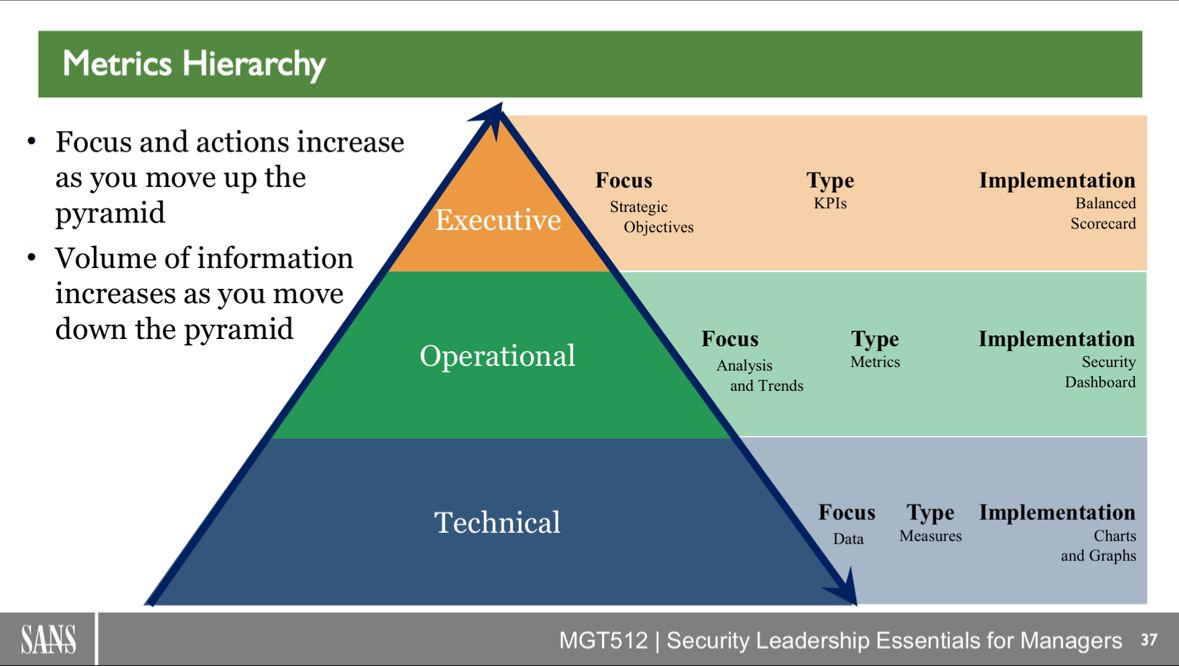

Frank Kim recently shared this lovely chart on LinkedIn. While it focuses on the differences between measures focused on data (at the Technical Level), compared to KPIs focused on strategic objectives (at the Executive Level), it captures an important nuance around communication: not only do you talk about different things at different levels, you’re going to use different vocabulary to do so.

But Fairy Tales?

The messages that security professionals need to convey have a lot in common with what fairy tales started out as: cautionary tales that encapsulated a set of hazards that your assets (generally, your children) were exposed to, as a way to instill caution in them (i.e., awareness training). So thinking about the point of fairy tales becomes a way to understand that we need to change how we communicate.

Aren’t Attack Paths Enough?

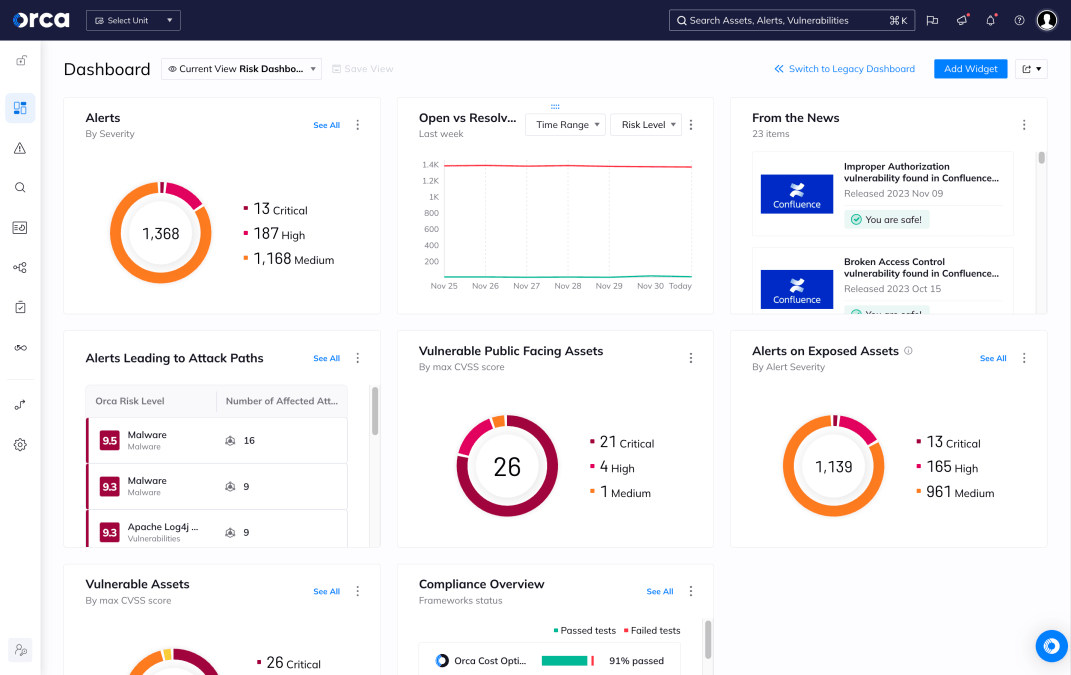

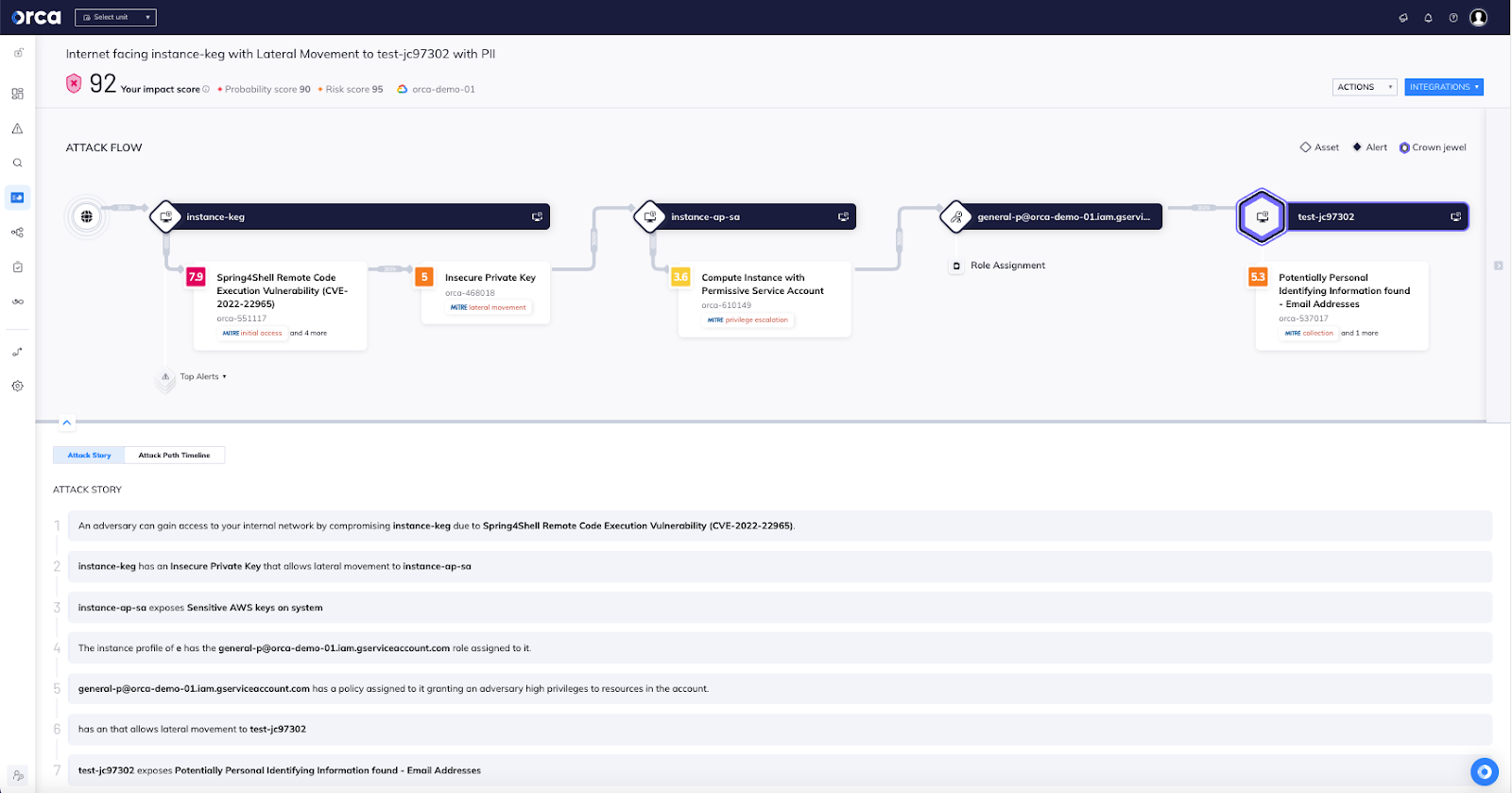

I love attack paths, don’t get me wrong. Let’s take a look at one:

Look at that: a 7-sentence story detailing exactly how an attacker could get from the Internet to a database with email addresses in it. That’s a really powerful view, and enables technical teams to discuss why overbroad permissions are dangerous, and to discuss PII’s presence in a test system. But put it in front of executives, especially in the C-suite or on the Board? This is an invitation for a disastrous conversation. Why? Because a board member is very different from a security architect.

Communication Styles: Security Architect or Board Member

A really good architect builds a complex mental model in their mind of the system that they’re responsible for. The more detailed, the better; it’s in the details that nuances about risk and the interactions between complex systems become visible and interesting. Architects bring this mental model with them, enriched with domain-specific knowledge. Mentioning that this attack path starts with a Spring4Shell probably brings to mind a dozen conversations the architect has had with developers about using the Spring framework, and each of those helps them make a more informed decision about what to do in this specific instance.

A really good executive is almost exactly the opposite. They have some rough mental models, but most of the time they are reacting to escalation, not proactively looking for issues. So as you start to talk to them about an issue, they have to reconstruct their mental model, almost from scratch (this is one reason quick refreshers are really powerful). Every word they don’t know? It’s another piece of their mental model that is missing, so they’re going to dig in on it. They hear the Spring framework, and, since they’ve never heard of it before, want to understand a lot of aspects of it: what it is, why we use it, what our support costs are, how we decided. The list of questions is never ending, but since you mentioned it, it now matters.

Conclusion: Executives Need Summaries

There are times when executives really do need a high level of detail, but it’s not the normal case. An architect looking at this one attack path might connect it in their head with a thousand other attack paths, and come to the conclusion that the company really ought to identify where their PII is, and maybe revisit their entitlements. It’s possible that revisiting the vulnerability remediation program is also on the table. With those three initiatives at play, it’s time to skip the technical details (unless asked), and drive right to the heart of the problem: There exist unacceptable losses that face the company (data loss), which are exposed by some unmitigated hazards (uncategorized data, broad entitlements, and poor software management), and which the company could address through strategic programs (data security posture management, cloud identity entitlements management, and vulnerability management).

Figuring out when to reduce the technical jargon and when to use it is one of the hardest challenges in bridging technical and executive communication, and I hope you join us at RSA to hear more about it!