The recent decision by the US Securities & Exchange Commission to require companies to report on cybersecurity risk and “material” incidents has led to a lot of discussion. Today, I want to avoid both whether this change is advisable (that ship has sailed) and interpreting specific sections such as how to determine that an incident is material (that’s a discussion for your lawyers); rather, I want to spend a little time on what we, as cloud cybersecurity practitioners, need to prepare for now.

There are two distinct sections of the final rule publication that should be of interest to us and I’m going to take them out of order.

Disclosure of a Registrant’s Risk Management, Strategy and Governance Regarding Cybersecurity Risks

17 CFR 229.106(b)(1) states:

Describe the registrant’s processes, if any, for assessing, identifying, and managing material risks from cybersecurity threats in sufficient detail for a reasonable investor to understand those processes.

Now, the truth here is that to report on a cybersecurity risk management program, you’ll have to have a documented cybersecurity risk management program. For those of us working in the cloud, our existing plan for on-premises systems rarely, if ever, extends to the things we’ve moved to the cloud.

Why would we need to adjust our plans to the cloud? To use the cloud in a (cost-)effective way, it’s necessary for organizations to embrace a number of changes that also change how we identify and address risks.

Differences in the Cloud Versus On-Prem

Ephemeral and Self-Service

One of the key value propositions of cloud computing is that it’s ephemeral; that is, resources can be created and destroyed without the requirement to buy, install, and manage physical infrastructure. In a data center, we have to order a new server, wait for it to be delivered, unbox it, wire it up, and configure it before we an use it; in contrast, if we’ve moved workloads to the cloud, anybody with the right permissions can do this, self-service, in a few minutes. This requires a fundamentally different approach to how we track our inventory of assets… and, if we don’t know what assets we have, we don’t know how to quantify their risk.

Declarative

As our cloud deployments mature, it makes sense to embrace declarative approaches where, instead of manually configuring new assets, they’re defined in code. This makes it easier to manage and scale in the cloud – if we need more servers, we can use the existing Terraform template to deploy more that are identical to the servers we already have – but it also changes how we remediate configuration issues. We can’t (or, at least, we shouldn’t) manually change the configuration of these resources. Rather, we need to change the Infrastructure-as-Code (IaC) templates that define how the assets are deployed and configured.

Cloud-Native Approaches

Organizations running in the cloud naturally adopt cloud-native approaches to building and running their services. This represents foundational changes in how we identify and remediate risks in those services.

For example, if we look at vulnerability management in a traditional data center and in a cloud-native deployment, there are several key differences. First, cloud-native approaches may use different types of deployments, such as containers or functions, where existing vulnerability assessment tools may not work well…or at all. We have to ensure that we are able to accurately assess the risk of these newer approaches.

Additionally, these approaches may fundamentally change how vulnerabilities are patched. In a traditional data center, fixing a critical vulnerability may require an operations engineer to patch a bunch of machines off-hours and, if necessary, reboot them. In our cloud-native, containerized approach, the running containers can’t be patched; rather, the dev owners of the container image would have to rebuild the image, retest it, reship it, and redeploy the containers based on the image.

Cloud Identity

Because of how identities and access are managed in the cloud, this is both a different and, typically, a more complex problem than managing identity and access on-prem. When organizations don’t plan for managing the complexity of cloud identity, they end up with a much larger attack surface.

Addressing Cloud Risk Management

While this is a complex problem that we can only start to address here, there are some foundational things that we should focus on.

Visibility

If we can’t identify risks for assets we don’t know we have, it stands to reason that any effective cloud risk management plan is going to start with discovering all of the ephemeral resources we have in our cloud(s). This should also cover all the different sorts of things we are moving to the cloud including resources we deploy in the cloud (VMs, clusters, functions, networks, etc), the workloads we run on top of those resources, cloud identity and access (with all its complexity), important data (whether it’s stored in buckets, databases, inside VMs, etc), and exposed endpoints.

Vulnerability Management

I’ve already talked about the difficulties of assessing and managing vulnerabilities in the cloud. It’s obviously important that any plan includes the ability to identify vulnerabilities, both before and after deployment, and to figure out the relative risk associated with the vulnerability (is it exploitable? Is it accessible? Does the vulnerable asset have access to sensitive data or powerful identities?)

Risk Identification

Vulnerabilities are far from the only risk that will impact our cloud estate. It’s critical to be able to identify the potential risks associated with misconfigurations across all of our cloud assets from storage to compute to networking to identity.

Risk Prioritization

The problem with being good at finding risks in the cloud is that there are, potentially, thousands of findings and organizations are unlikely to address them all. Being able to figure out which risks require immediate attention and which risks can be addressed in time is a key component of a cloud risk management plan. This prioritization should include a number of factors including but not limited to the criticality and exploitability of the risk itself, external exposure, access to sensitive data and identities, and potential impact to the business of an incident.

Disclosure of Cybersecurity Incidents

With few exceptions, the updated rule requires:

If the registrant experiences a cybersecurity incident that is determined by the registrant to be material, describe the material aspects of the nature, scope, and timing of the incident, and the material impact or reasonably likely material impact on the registrant, including its financial condition and results of operations.

While, as I wrote earlier, it’s up to your organization to figure out what might be seen as “material impact,” what is clear here is that security organizations will need to be in a position to quickly determine the extent and impact of a security incident after that determination has been made. There are many things that might be required to make a determination within the prescribed time frame but I want to talk through a few things that are critical to consider.

Before we continue, I should note that there was a change to clarify that companies aren’t required to “disclose any specific or technical information about their incident response, systems or potential vulnerabilities if that could impede their incident response and remediation process.” This does not change the necessities of detecting, investigating, and assessing the impact of any security incident, though; it just means that organizations don’t need to provide all the details in their disclosure when they detect a material breach.

Now, back to the key considerations regarding assessing the impact after a determination has been made for what constitutes “material.”

Threat Detection

Whether it’s malware scanning or detection of anomalous behavior by cloud identities, a comprehensive approach to threat detection is going to drive the investigation into a security incident, building out the timeline of what the attacker attempted and what they accomplished.

Data Visibility and Classifications

Many material security incidents will involve unauthorized access to data. If you don’t know what data lives in your cloud estate and how sensitive it is, you’ll have a hard time figuring out the potential impact of an incident.

Access Mapping (“Attack Paths”)

Security incidents are rarely contained to a single asset. Being able to understand how an incident might move between the asset you know is compromised and the rest of the estate is critical to guiding your investigation and, in the cloud, this can be complicated by the combination of multiple layers of network controls and the complexity of authentication and authorization.

Conclusion: Preparing for the SEC’s New Rules

Preparing to comply with the SEC’s new rules for disclosing risk management plans and materially significant security incidents is a large undertaking that requires people, process, and technology investments.

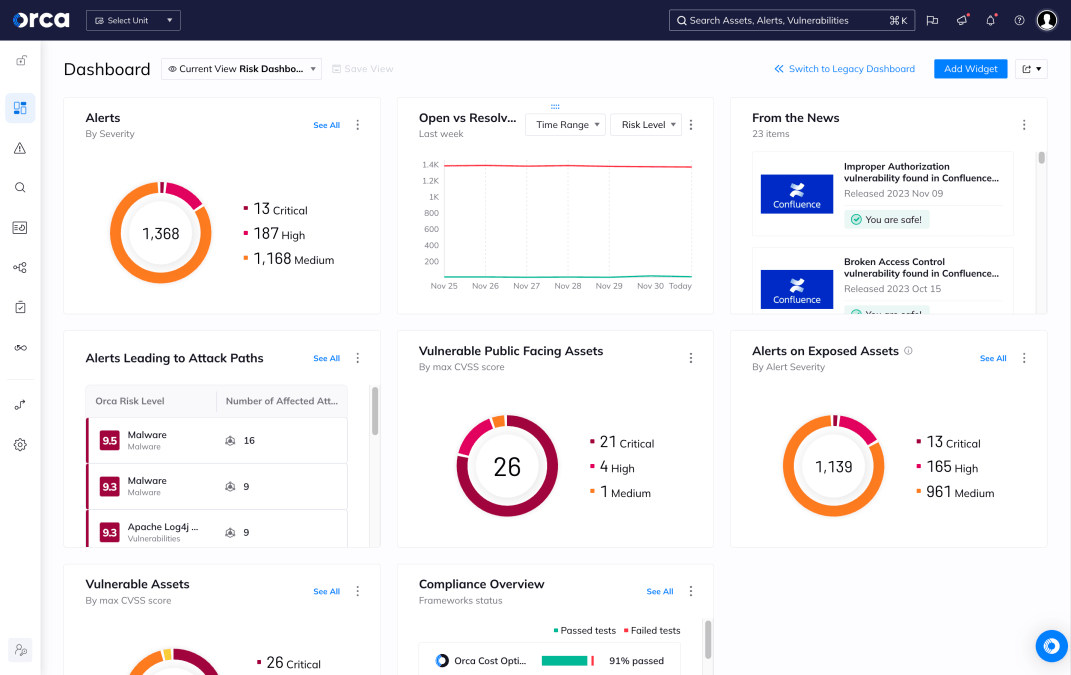

Employing a cloud native application protection platform (CNAPP) such as Orca Security can help your team achieve the holistic view of risk you need. As a result, the visibility you gain provides a clear starting point for mapping out your specific risk management plan while enabling you to get ahead of what to do in the case of an incident.

To see how Orca can help you get ahead of the new requirements, schedule a demo today.